by Matt Sheehan

by Matt SheehanOSF Healthcare

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

by Reilly Cook & Grace Friedman

by Reilly Cook & Grace Friedman

Tagged: PFAS found in firefighter gear, Health risks for firefighters, Illinois firefighters exposed to deadly chemical exposure, Making firefighting safer, Manufacturers would be banned from selling gear containing PFAS in Illinois

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

by John McCracken

by John McCrackenIn May, the Centers for Disease Control recommended that state public health departments, veterinarians and epidemiologists provide personal protective equipment, or PPE, for workers in direct contact with animals and their fluids, such as raw milk, that could be exposed to bird flu.

As of early December, almost 60 people have been infected with the virus, with the majority of cases stemming from human contact with dairy cattle. Nearly 700 dairy cattle herds have been infected.

The most effective way to protect workers is with face shields, latex gloves and respirators, the CDC advised.

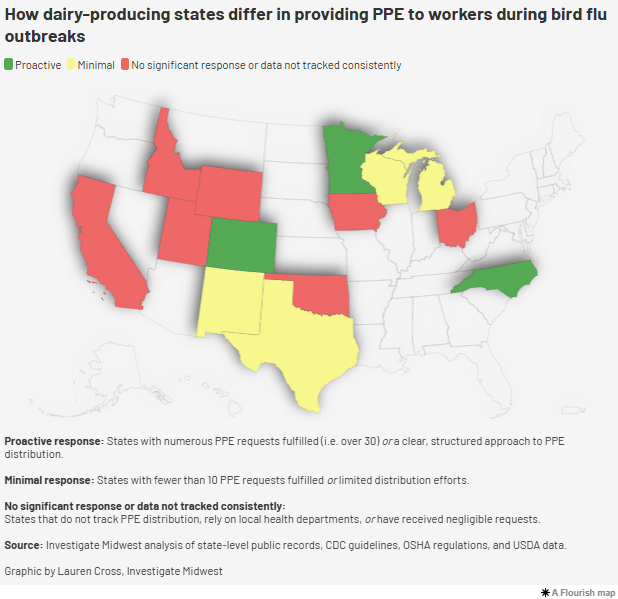

However, records from 15 states with confirmed cases of bird flu in dairy cattle reveal inconsistent responses by agencies when it comes to providing farmworkers with personal protective equipment. Most state health agencies, which are often responsible for the human impacts of communicable diseases, have left PPE distribution to local county health officials.

The documents, which Investigate Midwest obtained through multiple public records requests, found:

“It looks like a failure in how we’re communicating on the public health side to producers,” said Bethany Alcauter, director of research and public health for the National Center for Farmworker Health, a Texas-based nonprofit that provides resources and training to farmworkers and advocacy groups across the country.

Alcauter said farm operators and processors don’t have the same knowledge and outlook as public health officials because sick workers and animals are often part of the job.

“It’s not to say that they’re not getting sick, but because it’s maybe not that different from what they experience normally, it’s not going to change their perception of the risk just because it’s a different pathogen,” she said.

When dairy workers are milking cows, raw milk can come into contact with their hands, faces and bodies, increasing the risk of infection. The CDC advises that dairy workers wear PPE, including gloves, rubber overalls and face shields, to minimize the spread of the virus.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, OSHA, states that employers of workplaces where exposure to bird flu viruses could occur are responsible for providing PPE to workers and keeping records on infected animals and employees.

However, OSHA cannot enforce its standards on farms with less than 11 employees, an exemption that has harmed dairy workers in the past when dairy worker deaths and injuries went unreported. This makes the enforcement and responsibility of safety measures hard to pin down, Alcauter said.

“Workers are on their own in terms of actually enforcing anything,” she said.

In a recent CDC study, the agency said that the prevention of human infections is critical to mitigating changes in the bird flu virus that could lead to a pandemic.

Employers can best reduce the risk of infection by providing and educating workers on the use of PPE, as well as monitoring and testing animals and workers for the virus, the study said.

While PPE is a needed tool to prevent the spread, the practical application can be hard for workers who are working long hours and completing repetitive motion tasks in tight corners and hot environments.

Every worker who contracted the virus has been tasked with cleaning and working in milking parlors, according to the study.

After surveying the predominantly Spanish-speaking workers at Michigan and Colorado dairies, the agency found that none of the workers who were infected with the virus reported using PPE. In fact, the use of PPE was low among all workers.

“This investigation identified low PPE adherence among dairy workers, which has been an ongoing challenge in hot, tight spaces where visibility around large animals is important and the use of eye protection can be challenging,” the study states.

Records obtained by Investigate Midwest show inconsistent PPE distribution processes in both Michigan and Colorado, where dairy industries have been wrestling with the virus since early this year.

From January 2023 to late September 2024, records show only 11 dairy farms requested PPE for farmworkers in Michigan. Only 16 other operations requested PPE from the state during this time.

Farms that have requested PPE from the state have had an average of nine farmworkers per dairy farm, according to the self-reported request forms, which Investigate Midwest received through its records requests.

Conversely, the handful of poultry farms that have requested PPE have an average of 60 farmworkers per operation.

In Colorado, 40 dairy farms have requested PPE from the state agency between the beginning of 2023 and September 2024, according to documents and interviews with the agency.

Most requests came over the summer when Colorado started seeing repeated outbreaks of bird flu at dairy operations. As of early December, the state has had 64 confirmed cases in dairy herds.

The average number of dairy farmworkers operating on Colorado dairy farms that have requested PPE was roughly 40 people per farm.

“Some farms also reported that they had already purchased PPE and therefore didn’t need to make a request,” David Ellenberger, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, CDPHE, wrote in an email to Investigate Midwest.

“Additionally, CDPHE has sent bulk orders of PPE to an agricultural workers outreach group, who has relationships with individual workers, and was able to further distribute PPE on an individual level,” Ellenberger added.

Earlier this year, Texas was the first state in the country to have a confirmed case of bird flu in dairy cattle and, soon after, became the second site of mammal-to-human transmission of the virus in the country.

Since then, Texas has had nearly 30 cases of bird flu in cattle.

The state’s department of health has eight regional offices and it instructs farmers to contact their local office to request PPE.

“Each region fills them as they come in,” Texas spokesperson Douglas Loveday told Investigate Midwest.

In California, which now leads the country in the number of confirmed dairy cattle cases, the health and agriculture departments do not track or manage the distribution of PPE to farms and affected facilities. This task is left to the state’s 58 local health agencies.

In an email, a California Department of Public Health spokesperson said the state supported a one-time distribution of PPE to dairy farms earlier this year. When local requests can’t be fulfilled, the state agency fulfills the request.

As of early December, the agency has fulfilled or is currently fulfilling 43 PPE requests from dairy farms, six from poultry farms and 11 from farmworker organizations.

A similar system is used in Iowa and Idaho, which have also had numerous cases of bird flu in dairy cattle.

Ken Gordon, Ohio Department of Health spokesperson, told Investigate Midwest that when bird flu was detected in northwest Ohio earlier this year, the state made PPE available as the USDA investigated the outbreak. The state received two requests for PPE from agricultural operations during that time.

Now that the farm is no longer being investigated, the state is no longer offering PPE to farmworkers upon request.

“The state-level Ohio Department of Health made PPE available, via the survey, to farms and agricultural businesses on a temporary basis as the situation was new and evolving,” Gordon said.

Other states have received few requests or do not track disbursements:

North Carolina has one confirmed case of dairy cattle infected with bird flu. The state has also seen numerous cases of infected poultry, which is a major industry in the state.

One farm and four farmworkers requested PPE from the state during the ongoing outbreak. The majority of the state’s requests for PPE have come from farmworker organizations and advocacy groups.

The Association of Mexicans in North Carolina requested 2,000 face shields for dairy workers, stating that the association will make PPE available through health fairs aimed at farmworkers and contractors and their families held across the state.

In New Mexico, a state with nine confirmed outbreaks in dairy cattle, only two farms have requested PPE, according to state health department spokesperson David Morgan.

Some major agricultural states are preparing for outbreaks, even if a confirmed case hasn’t been reported.

In Wisconsin, a major dairy-producing state, the state health agency has received 11 requests for PPE from the beginning of 2023 to September of this year. The state has yet to have a confirmed case of bird flu in dairy cattle or humans.

Only one Wisconsin dairy farm and one egg production company have requested protective equipment for employees.

Most of the state’s requests have come from cheese or dairy product manufacturers in the state, as well as veterinary offices.

In addition to workers on farms with dairy cattle, employees who work in dairy processing plants are at risk of exposure to the virus. The CDC states that employees on dairy and poultry farms, dairy processing plants and poultry slaughter plants, should receive PPE to prevent the spread. The virus is destroyed when raw milk is pasteurized at a processing plant.

A spokesperson for Dairy Farmers of America, the country’s largest milk co-op and owner of nearly 50 dairy processing plants nationwide, told Investigate Midwest that the company has a safety protocol to provide PPE for workers at their plants.

DFA was not listed as a PPE recipient in the state of Wisconsin, where the company has three plants.

“PPE is (and was) standard protocol at our plants, prior to the bird flu, as many of our employees work around cleaning chemicals, “ a DFA spokesperson told Investigate Midwest in an email. “To date, we’ve had no requests for extra PPE.”

Wisconsin Department of Health Services spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt, said the agency has worked alongside the state’s agriculture department to provide updates about bird flu to producers, including information on how producers and industry groups can receive PPE.

“We know from our experience across public health that getting resources to agencies, organizations, and individuals who are most trusted by specific populations is the best way to share important information,” she said.

“Producers should continue to enhance their biosecurity efforts and monitor and control disease in their herds and flocks,” she said in an email to Investigate Midwest.

Minnesota’s Department of Public Health has fulfilled more than 200 requests for PPE since May despite the state having far fewer confirmed outbreaks in dairy cattle compared to its peers.

As of December, Minnesota has had 9 outbreaks in dairy cattle herds.

The majority of the state’s requests came from dairy producers, with 138 farms requesting. Twenty poultry farms requested PPE and nearly a dozen processing facilities, either dairy or poultry, requested equipment.

This story was originally published on Investigate Midwest. This article originally appeared in Sentient at https://sentientmedia.org/ppe-dairy-farm-workers-bird-flu/.

Investigate Midwest is an independent, nonprofit newsroom. Our mission is to serve the public interest by exposing dangerous and costly practices of influential agricultural corporations and institutions through in-depth and data-driven investigative journalism. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org

by Terri Dee

by Terri Dee by Arthur Allen and Eliza Fawcett, Healthbeat

by Arthur Allen and Eliza Fawcett, HealthbeatThe FDA has approved an updated covid shot for everyone 6 months old and up, which renews a now-annual quandary for Americans: Get the shot now, with the latest covid outbreak sweeping the country, or hold it in reserve for the winter wave?

The new vaccine should provide some protection to everyone. But many healthy people who have already been vaccinated or have immunity because they’ve been exposed to covid enough times may want to wait a few months.

Covid has become commonplace. For some, it’s a minor illness with few symptoms. Others are laid up with fever, cough, and fatigue for days or weeks. A much smaller group — mostly older or chronically ill people — suffer hospitalization or death.

It’s important for those in high-risk groups to get vaccinated, but vaccine protection wanes after a few months. Those who run to get the new vaccine may be more likely to fall ill this winter when the next wave hits, said William Schaffner, an infectious disease professor at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and a spokesperson for the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

On the other hand, by late fall the major variants may have changed, rendering the vaccine less effective, said Peter Marks, the FDA’s top vaccine official, at a briefing Aug. 23. He urged everyone eligible to get immunized, noting that the risk of long covid is greater in the un- and undervaccinated.

Of course, if last year’s covid vaccine rollout is any guide, few Americans will heed his advice, even though this summer’s surge has been unusually intense, with levels of the covid virus in wastewater suggesting infections are as widespread as they were in the winter.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now looks to wastewater as fewer people are reporting test results to health authorities. The wastewater data shows the epidemic is worst in Western and Southern states. In New York, for example, levels are considered “high” — compared with “very high” in Georgia.

Hospitalizations and deaths due to covid have trended up, too. But unlike infections, these rates are nowhere near those seen in winter surges, or in summers past. More than 2,000 people died of covid in July — a high number but a small fraction of the at least 25,700 covid deaths in July 2020.

Partial immunity built up through vaccines and prior infections deserves credit for this relief. A new study suggests that current variants may be less virulent — in the study, one of the recent variants did not kill mice exposed to it, unlike most earlier covid variants.

Public health officials note that even with more cases this summer, people seem to be managing their sickness at home. “We did see a little rise in the number of cases, but it didn’t have a significant impact in terms of hospitalizations and emergency room visits,” said Manisha Juthani, public health commissioner of Connecticut, at a news briefing Aug. 21.

Unlike influenza or traditional cold viruses, covid seems to thrive outside the cold months, when germy schoolkids, dry air, and indoor activities are thought to enable the spread of air- and saliva-borne viruses. No one is exactly sure why.

“Covid is still very transmissible, very new, and people congregate inside in air-conditioned rooms during the summer,” said John Moore, a virologist and professor at Cornell University’s Weill Cornell Medicine College.

Or “maybe covid is more tolerant of humidity or other environmental conditions in the summer,” said Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University.

Because viruses evolve as they infect people, the CDC has recommended updated covid vaccines each year. Last fall’s booster was designed to target the omicron variant circulating in 2023. This year, mRNA vaccines made by Moderna and Pfizer and the protein-based vaccine from Novavax — which has yet to be approved by the FDA — target a more recent omicron variant, JN.1.

The FDA determined that the mRNA vaccines strongly protected people from severe disease and death — and would do so even though earlier variants of JN.1 are now being overtaken by others.

Public interest in covid vaccines has waned, with only 1 in 5 adults getting vaccinated since last September, compared with about 80% who got the first dose. New Yorkers have been slightly above the national vaccination rate, while in Georgia only about 17% got the latest shot.

Vaccine uptake is lower in states where the majority voted for Donald Trump in 2020 and among those who have less money and education, less health care access, or less time off from work. These groups are also more likely to be hospitalized or die of the disease, according to a 2023 study in The Lancet.

While the newly formulated vaccines are better targeted at the circulating covid variants, uninsured and underinsured Americans may have to rush if they hope to get one for free. A CDC program that provided boosters to 1.5 million people over the last year ran out of money and is ending Aug. 31.

The agency drummed up $62 million in unspent funds to pay state and local health departments to provide the new shots to those not covered by insurance. But “that may not go very far” if the vaccine costs the agency around $86 a dose, as it did last year, said Kelly Moore, CEO of Immunize.org, which advocates for vaccination.

People who pay out-of-pocket at pharmacies face higher prices: CVS plans to sell the updated vaccine for $201.99, said Amy Thibault, a spokesperson for the company.

“Price can be a barrier, access can be a barrier” to vaccination, said David Scales, an assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Without an access program that provides vaccines to uninsured adults, “we’ll see disparities in health outcomes and disproportionate outbreaks in the working poor, who can ill afford to take off work,” Kelly Moore said.

New York state has about $1 million to fill the gaps when the CDC’s program ends, said Danielle De Souza, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health. That will buy around 12,500 doses for uninsured and underinsured adults, she said. There are roughly one million uninsured people in the state.

CDC and FDA experts last year decided to promote annual fall vaccination against covid and influenza along with a one-time respiratory syncytial virus shot for some groups.

It would be impractical for the vaccine-makers to change the covid vaccine’s recipe twice every year, and offering the three vaccines during one or two health care visits appears to be the best way to increase uptake of all of them, said Schaffner, who consults for the CDC’s policy-setting Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

At its next meeting, in October, the committee is likely to urge vulnerable people to get a second dose of the same covid vaccine in the spring, for protection against the next summer wave, he said.

If you’re in a vulnerable population and waiting to get vaccinated until closer to the holiday season, Schaffner said, it makes sense to wear a mask and avoid big crowds, and to get a test if you think you have covid. If positive, people in these groups should seek medical attention since the antiviral pill Paxlovid might ameliorate their symptoms and keep them out of the hospital.

As for conscientious others who feel they may be sick and don’t want to spread the covid virus, the best advice is to get a single test and, if positive, try to isolate for a few days and then wear a mask for several days while avoiding crowded rooms. Repeat testing after a positive result is pointless, since viral particles in the nose may remain for days without signifying a risk of infecting others, Schaffner said.

The Health and Human Services Department is making four free covid tests available to anyone who requests them starting in late September through covidtest.gov, said Dawn O’Connell, assistant secretary for preparedness and response, at the Aug. 23 briefing.

The government is focusing its fall vaccine advocacy campaign, which it’s calling “Risk less, live more,” on older people and nursing home residents, said HHS spokesperson Jeff Nesbit.

Not everyone may really need a fall covid booster, but “it’s not wrong to give people options,” John Moore said. “The 20-year-old athlete is less at risk than the 70-year-old overweight dude. It’s as simple as that.”

Healthbeat is a nonprofit newsroom covering public health published by Civic News Company and KFF Health News. Sign up for their newsletters here.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.Subscribe to KFF Health News' free Morning Briefing.

With a brief memo, Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo has subverted a public health standard that’s long kept measles outbreaks under control.

On Feb. 20, as measles spread through Manatee Bay Elementary in South Florida, Ladapo sent parents a letter granting them permission to send unvaccinated children to school amid the outbreak.

The Department of Health “is deferring to parents or guardians to make decisions about school attendance,” wrote Ladapo, who was appointed to head the agency by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whose name is listed above Ladapo’s in the letterhead.

Ladapo’s move contradicts advice from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This is not a parental rights issue,” said Scott Rivkees, Florida’s former surgeon general who is now a professor at Brown University. “It’s about protecting fellow classmates, teachers, and members of the community against measles, which is a very serious and very transmissible illness.”

Most people who aren’t protected by a vaccine will get measles if they’re exposed to the virus. This vulnerable group includes children whose parents don’t get them vaccinated, infants too young for the vaccine, those who can’t be vaccinated for medical reasons, and others who don’t mount a strong, lasting immune response to it. Rivkees estimates that about a tenth of people in a community fall into the vulnerable category.

The CDC advises that unvaccinated students stay home from school for three weeks after exposure. Because the highly contagious measles virus spreads on tiny droplets through the air and on surfaces, students are considered exposed simply by sitting in the same cafeteria or classroom as someone infected. And a person with measles can pass along an infection before they develop a fever, cough, rash, or other signs of the illness. About 1 in 5 people with measles end up hospitalized, 1 in 10 develop ear infections that can lead to permanent hearing loss, and about 1 in 1,000 die from respiratory and neurological complications.

“I don’t know why the health department wouldn’t follow the CDC recommendations,” said Thresia Gambon, president of the Florida chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics and a pediatrician who practices in Miami and Broward, the county affected by the current measles outbreak. “Measles is so contagious. It is very worrisome.”

Considering the dangers of the disease, the vaccine is incredibly safe. A person is about four times as likely to die from being struck by lightning during their lifetime in the United States as to have a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction to the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine.

Nonetheless, last year a record number of parents filed for exemptions from school vaccine requirements on religious or philosophical grounds across the United States. The CDC reported that childhood immunization rates hit a 10-year low.

In addition to Florida, measles cases have been reported in 11 other states this year, including Arizona, Georgia, Minnesota, and Virginia.

Only about a quarter of Florida’s counties had reached the 95% threshold at which communities are considered well protected against measles outbreaks, according to the most recent data posted by the Florida Department of Health in 2022. In Broward County, where six cases of measles have been reported over the past week, about 92% of children in kindergarten had received routine immunizations against measles, chickenpox, polio, and other diseases. The remaining 8% included more than 1,500 kids who had vaccine exemptions, as of 2022.

Broward’s local health department has been offering measles vaccines at Manatee Bay Elementary since the outbreak began, according to the county school superintendent. If an unvaccinated person gets a dose within three days of exposure to the virus, they’re far less likely to get measles and spread it to others.

For this reason, government officials have occasionally mandated vaccines in emergencies in the past. For example, Philadelphia’s deputy health commissioner in 1991 ordered children to get vaccinated against their parents’ wishes during outbreaks traced to their faith-healing churches. And during a large measles outbreak among Orthodox Jewish communities in Brooklyn in 2019, the New York City health commissioner mandated that anyone who lived, worked, or went to school in hard-hit neighborhoods get vaccinated or face a fine of $1,000. In that ordinance, the commissioner wrote that the presence of anyone lacking the vaccine in those areas, unless it was medically contraindicated, “creates an unnecessary and avoidable risk of continuing the outbreak.”

Ladapo moved in the opposite direction with his letter, deferring to parents because of the “high immunity rate in the community,” which data contradicts, and because of the “burden on families and educational cost of healthy children missing school.”

Yet the burden of an outbreak only grows larger as cases of measles spread, requiring more emergency care, more testing, and broader quarantines as illness and hospitalizations mount. Curbing a 2018 outbreak in southern Washington with 72 cases cost about $2.3 million, in addition to $76,000 in medical costs, and an estimated $1 million in economic losses due to illness, quarantine, and caregiving. If numbers soar, death becomes a burden, too. An outbreak among a largely unvaccinated population in Samoa caused more than 5,700 cases and 83 deaths, mainly among children.

Ladapo’s letter to parents also marks a departure from the norm because local health departments tend to take the lead on containing measles outbreaks, rather than state or federal authorities. In response to queries from KFF Health News, Broward County’s health department deferred to Florida’s state health department, which Ladapo oversees.

“The county doesn’t have the power to disagree with the state health department,” said Rebekah Jones, a data scientist who was removed from her post at the Florida health department in 2020, over a rift regarding coronavirus data.

DeSantis, a Republican, appointed Ladapo as head of the state health department in late 2021, as DeSantis integrated skepticism about covid vaccines into his political platform. In the months that followed, Florida’s health department removed information on covid vaccines from its homepage, and reprimanded a county health director for encouraging his staff to get the vaccines, leading to his resignation. In January, the health department website posted Ladapo’s call to halt vaccination with covid mRNA vaccines entirely, based on notions that scientists call implausible.

Jones was not surprised to see Ladapo pivot to measles. “I think this is the predictable outcome of turning fringe, anti-vaccine rhetoric into a defining trait of the Florida government,” she said. Although his latest decision runs contrary to CDC advice, the federal agency rarely intervenes in measles outbreaks, entrusting the task to states.

In an email to KFF Health News, the Florida health department said it was working with others to identify the contacts of people with measles, but that details on cases and places of exposure were confidential. It repeated Ladapo’s decision, adding, “The surgeon general’s recommendation may change as epidemiological investigations continue.”

For Gambon, the outbreak is already disconcerting. “I would like to see the surgeon general promote what is safest for children and for school staff,” she said, “since I am sure there are many who might not have as strong immunity as we would hope.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

From domed ceilings to legendary alumni, a new book explores the most unique high school basketball gyms in Illinois through st...