by Matt Sheehan

by Matt SheehanOSF Healthcare

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

Five years after the first news of COVID, recent reports of an obscure respiratory virus in China may understandably raise concerns.

Chinese authorities first issued warnings about human metapneumovirus (hMPV) in 2023, but media reports indicate cases may be increasing again during China’s winter season.

For most people, hMPV will cause symptoms similar to a cold or the flu. In rare cases, hMPV can lead to severe infections. But it isn’t likely to cause the next pandemic.

hMPV was first discovered in 2001 by scientists from the Netherlands in a group of children where tests for other known respiratory viruses were negative.

But it was probably around long before that. Testing of samples from the 1950s demonstrated antibodies against this virus, suggesting infections have been common for at least several decades. Studies since have found hMPV in almost all regions in the world.

Australian data prior to the COVID pandemic found hMPV to be the third most common virus detected in adults and children with respiratory infections. In adults, the two most common were influenza and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus), while in children they were RSV and parainfluenza.

Like influenza, hMPV is a more significant illness for younger and older people.

Studies suggest most children are exposed early in life, with the majority of children by age five having antibodies indicating prior infection. In general, this reduces the severity of subsequent infections for older children and adults.

In young children, hMPV most commonly causes infections of the upper respiratory tract, with symptoms including runny nose, sore throat, fever as well as ear infections. These symptoms usually resolve over a few days to a week in children, and 1–2 weeks in adults.

Although most infections with hMPV are relatively mild, it can cause more severe disease in people with underlying medical conditions, such as heart disease. Complications can include pneumonia, with shortness of breath, fever and wheezing. hMPV can also worsen pre-existing lung diseases such as asthma or emphysema. Additionally, infection can be serious in people with weakened immune systems, particularly those who have had bone marrow or lung transplants.

But the generally mild nature of the illness, the widespread detection of antibodies reflecting broad population exposure and immunity, combined with a lack of any known major pandemics in the past due to hMPV, suggests there’s no cause for alarm.

It is presumed that hMPV is transmitted by contact with respiratory secretions, either through the air or on contaminated surfaces. Therefore, personal hygiene measures and avoiding close contact with other people while unwell should reduce the risk of transmission.

The virus is a distant cousin of RSV for which immunisation products have recently become available, including vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. This has led to the hope that similar products may be developed for hMPV, and Moderna has recently started trials into a mRNA hMPV vaccine.

There are no treatments that have been clearly demonstrated to be effective. But for severely unwell patients certain antivirals may offer some benefit.

Since the COVID pandemic, the pattern of many respiratory infections has changed. For example, in Australia, influenza seasons have started earlier (peaking in June–July rather than August–September).

Many countries, including Australia, are reporting an increased number of cases of whooping cough (pertussis).

In China, there have been reports of increased cases of mycoplasma, a bacterial cause of pneumonia, as well as influenza and hMPV.

There are many factors that may have impacted the epidemiology of respiratory pathogens. These include the interruption to respiratory virus transmission due to public health measures taken during the COVID pandemic, environmental factors such as climate change, and for some diseases, post-pandemic changes in vaccine coverage. It may also be the usual variation we see with respiratory infections – for example, pertussis outbreaks are known to occur every 3–4 years.

For hMPV in Australia, we don’t yet have stable surveillance systems to form a good picture of what a “usual” hMPV season looks like. So with international reports of outbreaks, it will be important to monitor the available data for hMPV and other respiratory viruses to inform local public health policy.

Allen Cheng, Professor of Infectious Diseases, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by John McCracken

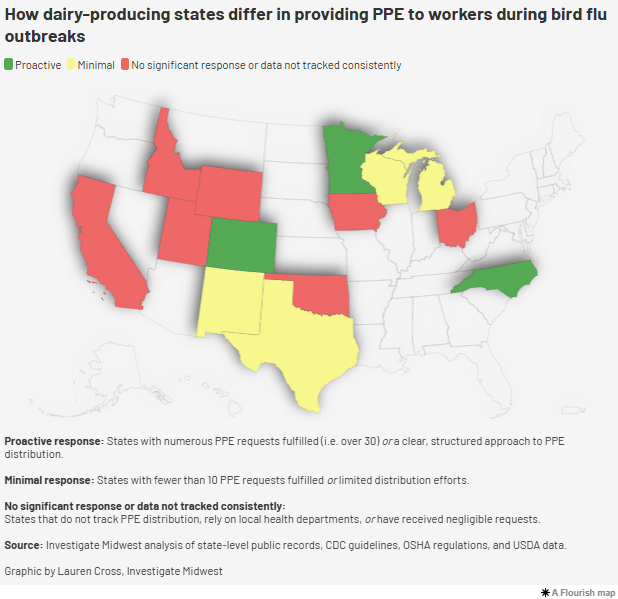

by John McCrackenIn May, the Centers for Disease Control recommended that state public health departments, veterinarians and epidemiologists provide personal protective equipment, or PPE, for workers in direct contact with animals and their fluids, such as raw milk, that could be exposed to bird flu.

As of early December, almost 60 people have been infected with the virus, with the majority of cases stemming from human contact with dairy cattle. Nearly 700 dairy cattle herds have been infected.

The most effective way to protect workers is with face shields, latex gloves and respirators, the CDC advised.

However, records from 15 states with confirmed cases of bird flu in dairy cattle reveal inconsistent responses by agencies when it comes to providing farmworkers with personal protective equipment. Most state health agencies, which are often responsible for the human impacts of communicable diseases, have left PPE distribution to local county health officials.

The documents, which Investigate Midwest obtained through multiple public records requests, found:

“It looks like a failure in how we’re communicating on the public health side to producers,” said Bethany Alcauter, director of research and public health for the National Center for Farmworker Health, a Texas-based nonprofit that provides resources and training to farmworkers and advocacy groups across the country.

Alcauter said farm operators and processors don’t have the same knowledge and outlook as public health officials because sick workers and animals are often part of the job.

“It’s not to say that they’re not getting sick, but because it’s maybe not that different from what they experience normally, it’s not going to change their perception of the risk just because it’s a different pathogen,” she said.

When dairy workers are milking cows, raw milk can come into contact with their hands, faces and bodies, increasing the risk of infection. The CDC advises that dairy workers wear PPE, including gloves, rubber overalls and face shields, to minimize the spread of the virus.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, OSHA, states that employers of workplaces where exposure to bird flu viruses could occur are responsible for providing PPE to workers and keeping records on infected animals and employees.

However, OSHA cannot enforce its standards on farms with less than 11 employees, an exemption that has harmed dairy workers in the past when dairy worker deaths and injuries went unreported. This makes the enforcement and responsibility of safety measures hard to pin down, Alcauter said.

“Workers are on their own in terms of actually enforcing anything,” she said.

In a recent CDC study, the agency said that the prevention of human infections is critical to mitigating changes in the bird flu virus that could lead to a pandemic.

Employers can best reduce the risk of infection by providing and educating workers on the use of PPE, as well as monitoring and testing animals and workers for the virus, the study said.

While PPE is a needed tool to prevent the spread, the practical application can be hard for workers who are working long hours and completing repetitive motion tasks in tight corners and hot environments.

Every worker who contracted the virus has been tasked with cleaning and working in milking parlors, according to the study.

After surveying the predominantly Spanish-speaking workers at Michigan and Colorado dairies, the agency found that none of the workers who were infected with the virus reported using PPE. In fact, the use of PPE was low among all workers.

“This investigation identified low PPE adherence among dairy workers, which has been an ongoing challenge in hot, tight spaces where visibility around large animals is important and the use of eye protection can be challenging,” the study states.

Records obtained by Investigate Midwest show inconsistent PPE distribution processes in both Michigan and Colorado, where dairy industries have been wrestling with the virus since early this year.

From January 2023 to late September 2024, records show only 11 dairy farms requested PPE for farmworkers in Michigan. Only 16 other operations requested PPE from the state during this time.

Farms that have requested PPE from the state have had an average of nine farmworkers per dairy farm, according to the self-reported request forms, which Investigate Midwest received through its records requests.

Conversely, the handful of poultry farms that have requested PPE have an average of 60 farmworkers per operation.

In Colorado, 40 dairy farms have requested PPE from the state agency between the beginning of 2023 and September 2024, according to documents and interviews with the agency.

Most requests came over the summer when Colorado started seeing repeated outbreaks of bird flu at dairy operations. As of early December, the state has had 64 confirmed cases in dairy herds.

The average number of dairy farmworkers operating on Colorado dairy farms that have requested PPE was roughly 40 people per farm.

“Some farms also reported that they had already purchased PPE and therefore didn’t need to make a request,” David Ellenberger, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, CDPHE, wrote in an email to Investigate Midwest.

“Additionally, CDPHE has sent bulk orders of PPE to an agricultural workers outreach group, who has relationships with individual workers, and was able to further distribute PPE on an individual level,” Ellenberger added.

Earlier this year, Texas was the first state in the country to have a confirmed case of bird flu in dairy cattle and, soon after, became the second site of mammal-to-human transmission of the virus in the country.

Since then, Texas has had nearly 30 cases of bird flu in cattle.

The state’s department of health has eight regional offices and it instructs farmers to contact their local office to request PPE.

“Each region fills them as they come in,” Texas spokesperson Douglas Loveday told Investigate Midwest.

In California, which now leads the country in the number of confirmed dairy cattle cases, the health and agriculture departments do not track or manage the distribution of PPE to farms and affected facilities. This task is left to the state’s 58 local health agencies.

In an email, a California Department of Public Health spokesperson said the state supported a one-time distribution of PPE to dairy farms earlier this year. When local requests can’t be fulfilled, the state agency fulfills the request.

As of early December, the agency has fulfilled or is currently fulfilling 43 PPE requests from dairy farms, six from poultry farms and 11 from farmworker organizations.

A similar system is used in Iowa and Idaho, which have also had numerous cases of bird flu in dairy cattle.

Ken Gordon, Ohio Department of Health spokesperson, told Investigate Midwest that when bird flu was detected in northwest Ohio earlier this year, the state made PPE available as the USDA investigated the outbreak. The state received two requests for PPE from agricultural operations during that time.

Now that the farm is no longer being investigated, the state is no longer offering PPE to farmworkers upon request.

“The state-level Ohio Department of Health made PPE available, via the survey, to farms and agricultural businesses on a temporary basis as the situation was new and evolving,” Gordon said.

Other states have received few requests or do not track disbursements:

North Carolina has one confirmed case of dairy cattle infected with bird flu. The state has also seen numerous cases of infected poultry, which is a major industry in the state.

One farm and four farmworkers requested PPE from the state during the ongoing outbreak. The majority of the state’s requests for PPE have come from farmworker organizations and advocacy groups.

The Association of Mexicans in North Carolina requested 2,000 face shields for dairy workers, stating that the association will make PPE available through health fairs aimed at farmworkers and contractors and their families held across the state.

In New Mexico, a state with nine confirmed outbreaks in dairy cattle, only two farms have requested PPE, according to state health department spokesperson David Morgan.

Some major agricultural states are preparing for outbreaks, even if a confirmed case hasn’t been reported.

In Wisconsin, a major dairy-producing state, the state health agency has received 11 requests for PPE from the beginning of 2023 to September of this year. The state has yet to have a confirmed case of bird flu in dairy cattle or humans.

Only one Wisconsin dairy farm and one egg production company have requested protective equipment for employees.

Most of the state’s requests have come from cheese or dairy product manufacturers in the state, as well as veterinary offices.

In addition to workers on farms with dairy cattle, employees who work in dairy processing plants are at risk of exposure to the virus. The CDC states that employees on dairy and poultry farms, dairy processing plants and poultry slaughter plants, should receive PPE to prevent the spread. The virus is destroyed when raw milk is pasteurized at a processing plant.

A spokesperson for Dairy Farmers of America, the country’s largest milk co-op and owner of nearly 50 dairy processing plants nationwide, told Investigate Midwest that the company has a safety protocol to provide PPE for workers at their plants.

DFA was not listed as a PPE recipient in the state of Wisconsin, where the company has three plants.

“PPE is (and was) standard protocol at our plants, prior to the bird flu, as many of our employees work around cleaning chemicals, “ a DFA spokesperson told Investigate Midwest in an email. “To date, we’ve had no requests for extra PPE.”

Wisconsin Department of Health Services spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt, said the agency has worked alongside the state’s agriculture department to provide updates about bird flu to producers, including information on how producers and industry groups can receive PPE.

“We know from our experience across public health that getting resources to agencies, organizations, and individuals who are most trusted by specific populations is the best way to share important information,” she said.

“Producers should continue to enhance their biosecurity efforts and monitor and control disease in their herds and flocks,” she said in an email to Investigate Midwest.

Minnesota’s Department of Public Health has fulfilled more than 200 requests for PPE since May despite the state having far fewer confirmed outbreaks in dairy cattle compared to its peers.

As of December, Minnesota has had 9 outbreaks in dairy cattle herds.

The majority of the state’s requests came from dairy producers, with 138 farms requesting. Twenty poultry farms requested PPE and nearly a dozen processing facilities, either dairy or poultry, requested equipment.

This story was originally published on Investigate Midwest. This article originally appeared in Sentient at https://sentientmedia.org/ppe-dairy-farm-workers-bird-flu/.

Investigate Midwest is an independent, nonprofit newsroom. Our mission is to serve the public interest by exposing dangerous and costly practices of influential agricultural corporations and institutions through in-depth and data-driven investigative journalism. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org

by Matt Sheehan

by Matt Sheehan

Meggan Ingram was fully vaccinated when she tested positive for COVID-19 early this month. The 37-year-old’s fever had spiked to 103 and her breath was coming in ragged bursts when an ambulance rushed her to an emergency room in Pasco, Washington, on Aug. 10. For three hours she was given oxygen and intravenous steroids, but she was ultimately sent home without being admitted.

Seven people in her house have now tested positive. Five were fully vaccinated and two of the children are too young to get a vaccine.

As the pandemic enters a critical new phase, public health authorities continue to lack data on crucial questions, just as they did when COVID-19 first tore through the United States in the spring of 2020. Today there remains no full understanding on how the aggressively contagious delta variant spreads among the nearly 200 million partially or fully vaccinated Americans like Ingram, or on how many are getting sick.

The nation is flying blind yet again, critics say, because on May 1 of this year — as the new variant found a foothold in the U.S. — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mostly stopped tracking COVID-19 in vaccinated people, also known as breakthrough cases, unless the illness was severe enough to cause hospitalization or death.

Individual states now set their own criteria for collecting data on breakthrough cases, resulting in a muddled grasp of COVID-19’s impact, leaving experts in the dark as to the true number of infections among the vaccinated, whether or not vaccinated people can develop long-haul illness, and the risks to unvaccinated children as they return to school.

"It’s like saying we don’t count,” said Ingram after learning of the CDC’s policy change. COVID-19 roared through her household, yet it is unlikely any of those cases will show up in federal data because no one died or was admitted to a hospital.

The CDC told ProPublica in an email that it continues to study breakthrough cases, just in a different way. "This shift will help maximize the quality of the data collected on cases of greatest clinical and public health importance,” the email said.

In addition to the hospitalization and death information, the CDC is working with Emerging Infections Program sites in 10 states to study breakthrough cases, including some mild and asymptomatic ones, the agency’s email said.

Under pressure from some health experts, the CDC announced Wednesday that it will create a new outbreak analysis and forecast center, tapping experts in the private sector and public health to guide it to better predict how diseases spread and to act quickly during an outbreak.

Tracking only some data and not releasing it sooner or more fully, critics say, leaves a gaping hole in the nation’s understanding of the disease at a time when it most needs information.

"They are missing a large portion of the infected," said Dr. Randall Olsen, medical director of molecular diagnostics at Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas. "If you’re limiting yourself to a small subpopulation with only hospitalizations and deaths, you risk a biased viewpoint."

On Wednesday, the CDC released a trio of reports that found that while the vaccine remained effective at keeping vaccinated people out of the hospital, the overall protection appears to be waning over time, especially against the delta variant.

Among nursing home residents, one of the studies showed vaccine effectiveness dropped from 74.7% in the spring to just 53.1% by midsummer. Similarly, another report found that the overall effectiveness among vaccinated New York adults dropped from 91.7% to just under 80% between May and July.

The new findings prompted the Biden administration to announce on Wednesday that people who got a Moderna or Pfizer vaccine will be offered a booster shot eight months after their second dose. The program is scheduled to begin the week of Sept. 20 but needs approval from the Food and Drug Administration and a CDC advisory committee.

This latest development is seen by some as another example of shifting public health messaging and backpedaling that has accompanied every phase of the pandemic for 19 months through two administrations. A little more than a month ago, the CDC and the FDA released a joint statement saying that those who have been fully vaccinated "do not need a booster shot at this time.”

The vaccine rollout late last year came with cautious optimism. No vaccine is 100% percent effective against transmission, health officials warned, but the three authorized vaccines proved exceedingly effective against the original COVID-19 strain. The CDC reported a breakthrough infection rate of 0.01% for the months between January and the end of April, although it acknowledged it could be an undercount.

As summer neared, the White House signaled it was time for the vaccinated to celebrate and resume their pre-pandemic lives.

Trouble, though, was looming. Outbreaks of a new, highly contagious variant swept India in the spring and soon began to appear in other nations. It was only a matter of time before it struck here, too.

"The world changed," said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, "when delta invaded."

The current crush of U.S. cases — well over 100,000 per day — has hit the unvaccinated by far the hardest, leaving them at greater risk of serious illness or death. The delta variant is considered at least two or three times more infectious than the original strain of the coronavirus. For months much of the focus by health officials and the White House has been on convincing the resistant to get vaccinated, an effort that has so far produced mixed results.

Yet as spring turned to summer, scattered reports surfaced of clusters of vaccinated people testing positive for the coronavirus. In May, eight vaccinated members of the New York Yankees tested positive. In June, 11 employees of a Las Vegas hospital became infected, eight of whom were fully vaccinated. And then 469 people who visited the Provincetown, Massachusetts, area between July 3 and July 17 became infected even though 74% of them were fully vaccinated, according to the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

While the vast majority of those cases were relatively mild, the Massachusetts outbreak contributed to the CDC reversing itself on July 27 and recommending that even vaccinated people wear masks indoors — 11 weeks after it had told them they could jettison the protection.

And as the new CDC data showed, vaccines continue to effectively shield vaccinated people against the worst outcomes. But those who get the virus are, in fact, often miserably sick and may chafe at the notion that their cases are not being fully counted.

"The vaccinated are not as protected as they think," said Topol, "They are still in jeopardy."

The CDC tracked all breakthrough cases until the end of April, then abruptly stopped without making a formal announcement. A reference to the policy switch appeared on the agency’s website in May about halfway down the homepage.

"I was shocked," said Dr. Leana Wen, a physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University. "I have yet to hear a coherent explanation of why they stopped tracking this information.”

The CDC said in an emailed statement to ProPublica that it decided to focus on the most serious cases because officials believed more targeted data collection would better inform "response research, decisions, and policy."

Sen. Edward MMarkey, D-Mass., became alarmed after the Provincetown outbreak and wrote to CDC director Dr. Rochelle Walensky on July 22, questioning the decision to limit investigation of breakthrough cases. He asked what type of data was being compiled and how it would be shared publicly.

"The American public must be informed of the continued risk posed by COVID-19 and variants, and public health and medical officials, as well as health care providers, must have robust data and information to guide their decisions on public health measures," the letter said.

Markey asked the agency to respond by Aug. 12. So far the senator has received no reply, and the CDC did not answer ProPublica’s question about it.

When the CDC halted its tracking of all but the most severe cases, local and state health departments were left to make up their own rules.

There is now little consistency from state to state or even county to county on what information is gathered about breakthrough cases, how often it is publicly shared, or if it is shared at all.

"We’ve had a patchwork of information between states since the beginning of the pandemic,” said Jen Kates, senior vice president and director of global health and HIV policy at Kaiser Family Foundation.

She is co-author of a July 30 study that found breakthrough cases across the U.S. remained rare, especially those leading to hospitalization or death. However, the study acknowledged that information was limited because state reporting was spotty. Only half the states provide some data on COVID-19 illnesses in vaccinated people.

"There is no single, public repository for data by state or data on breakthrough infections, since the CDC stopped monitoring them,” the report said.

In Texas, where COVID-19 cases are skyrocketing, a state Health and Human Services Commission spokesperson told ProPublica in an email the state agency was "collecting COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough cases of heightened public health interest that result in hospitalization or fatality only."

Other breakthrough case information is not tracked by the state, so it is unclear how often breakthroughs occur or how widely cases are spreading among the vaccinated. And while Texas reports breakthrough deaths and hospitalizations to the CDC, the information is not included on the state’s public dashboard.

"We will be making some additions to what we are posting, and these data could be included in the future," the spokesperson said.South Carolina, on the other hand, makes public its breakthrough numbers on hospitalizations and deaths. Milder breakthrough cases may be included in the state’s overall COVID-19 numbers but they are not labeled as such, said Jane Kelly, an epidemiologist at the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control.

"We agree with the CDC,” she said, "there’s no need to spend public health resources investigating every asymptomatic or mild infection.”

In Utah, state health officials take a different view. "From the beginning of the pandemic we have been committed to being transparent with our data reporting and … the decision to include breakthrough case data on our website is consistent with that approach," said Tom Hudachko, director of communications for the Utah Department of Health.

Some county-level officials said they track as many breakthrough cases as possible even if their state and the CDC does not.

For instance, in Clark County, Nevada, home of Las Vegas, the public health website reported that as of last week there were 225 hospitalized breakthrough cases but 4,377 vaccinated people overall who have tested positive for the coronavirus.

That means that less than 5% of reported breakthrough cases resulted in hospitalization. "The Southern Nevada Health District tracks the total number of fully vaccinated individuals who test positive for COVID-19 and it is a method to provide a fuller picture of what is occurring in our community,” said Stephanie Bethel, a spokesperson for the health district in an email.

Sara Schmidt, a 44-year-old elementary school teacher in Alton, Illinois, is another person who has likely fallen through the data hole.

"I thought, ‘COVID is over and I’m going to Disney World,’" she said. She planned a five-day trip for the end of July with her parents. Not only had she been fully vaccinated, receiving her second shot in March, she is also sure she had COVID-19 in the summer of 2020. Back then she had all the symptoms but had a hard time getting tested. When she finally did, the result came back negative, but her doctor told her to assume it was inaccurate.

"My guard was down," she said. She was less vigilant about wearing a mask in the Florida summer heat, assuming she was protected by the vaccination and her presumed earlier infection.

On the July 29 plane trip home, she felt mildly sick. Within days she was "absolutely miserable." Her coughing continued to worsen, and each time she coughed her head pounded. On Aug. 1 she tested positive. Her parents were negative.

Now, three weeks later, she is far from fully recovered and classes are about to begin at her school. There’s a school mask mandate, but her students are too young to be vaccinated. "I’m worried I will give it to them, or I will get it for a third time," she said.

But it is doubtful her case will be tracked because she was never hospitalized. That infuriates her, she said, because it downplays what is happening.

"Everyone has a right to know how many breakthrough cases there are," she said, "I was under the impression that if I did get a breakthrough case, it would just be sniffles. They make it sound like everything is under control and it’s not."

This story was originally published by ProPublica on August 20, 2021. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Konstantin Zhukov says that an FBI raid of a journalist’s home last week is not an isolated incident but part of an ongoing escalation si...