by John McCracken

by John McCrackenInvestigate Midwest

In May, the Centers for Disease Control recommended that state public health departments, veterinarians and epidemiologists provide personal protective equipment, or PPE, for workers in direct contact with animals and their fluids, such as raw milk, that could be exposed to bird flu.

As of early December, almost 60 people have been infected with the virus, with the majority of cases stemming from human contact with dairy cattle. Nearly 700 dairy cattle herds have been infected.

The most effective way to protect workers is with face shields, latex gloves and respirators, the CDC advised.

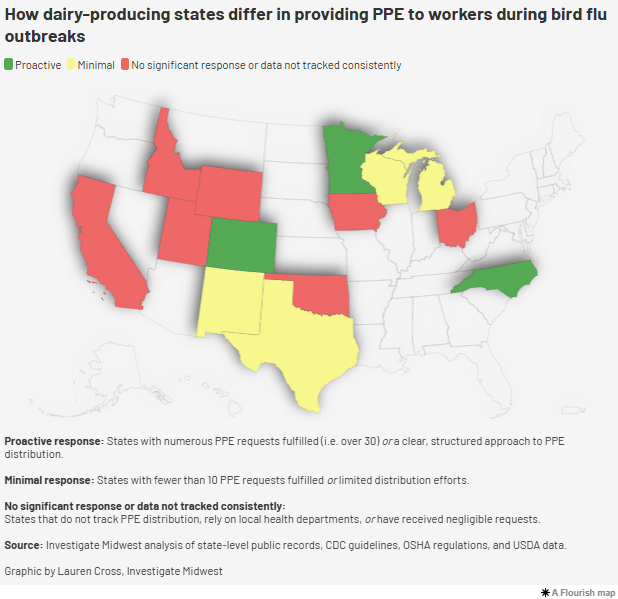

However, records from 15 states with confirmed cases of bird flu in dairy cattle reveal inconsistent responses by agencies when it comes to providing farmworkers with personal protective equipment. Most state health agencies, which are often responsible for the human impacts of communicable diseases, have left PPE distribution to local county health officials.

The documents, which Investigate Midwest obtained through multiple public records requests, found:

- At least a third of state health departments in states with confirmed dairy cattle outbreaks do not track the distribution of PPE.

- Ohio, Wyoming and New Mexico, which have had active bird flu cases in dairy cattle, have either not tracked requests for farmworker PPE or are currently not accepting requests.

- Only one dairy farm in Wisconsin, a major dairy state that has not had a confirmed cattle outbreak, has requested PPE from the state’s health department.

- Minnesota has had few cases of bird flu in dairy cattle, but more than 200 agriculture businesses have received PPE from the state.

- Michigan and North Carolina, which are also major dairy-producing states, have provided PPE to less than a dozen farms.

“It looks like a failure in how we’re communicating on the public health side to producers,” said Bethany Alcauter, director of research and public health for the National Center for Farmworker Health, a Texas-based nonprofit that provides resources and training to farmworkers and advocacy groups across the country.

Alcauter said farm operators and processors don’t have the same knowledge and outlook as public health officials because sick workers and animals are often part of the job.

“It’s not to say that they’re not getting sick, but because it’s maybe not that different from what they experience normally, it’s not going to change their perception of the risk just because it’s a different pathogen,” she said.

When dairy workers are milking cows, raw milk can come into contact with their hands, faces and bodies, increasing the risk of infection. The CDC advises that dairy workers wear PPE, including gloves, rubber overalls and face shields, to minimize the spread of the virus.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, OSHA, states that employers of workplaces where exposure to bird flu viruses could occur are responsible for providing PPE to workers and keeping records on infected animals and employees.

However, OSHA cannot enforce its standards on farms with less than 11 employees, an exemption that has harmed dairy workers in the past when dairy worker deaths and injuries went unreported. This makes the enforcement and responsibility of safety measures hard to pin down, Alcauter said.

“Workers are on their own in terms of actually enforcing anything,” she said.

In a recent CDC study, the agency said that the prevention of human infections is critical to mitigating changes in the bird flu virus that could lead to a pandemic.

Employers can best reduce the risk of infection by providing and educating workers on the use of PPE, as well as monitoring and testing animals and workers for the virus, the study said.

While PPE is a needed tool to prevent the spread, the practical application can be hard for workers who are working long hours and completing repetitive motion tasks in tight corners and hot environments.

Every worker who contracted the virus has been tasked with cleaning and working in milking parlors, according to the study.

After surveying the predominantly Spanish-speaking workers at Michigan and Colorado dairies, the agency found that none of the workers who were infected with the virus reported using PPE. In fact, the use of PPE was low among all workers.

“This investigation identified low PPE adherence among dairy workers, which has been an ongoing challenge in hot, tight spaces where visibility around large animals is important and the use of eye protection can be challenging,” the study states.

Records obtained by Investigate Midwest show inconsistent PPE distribution processes in both Michigan and Colorado, where dairy industries have been wrestling with the virus since early this year.

From January 2023 to late September 2024, records show only 11 dairy farms requested PPE for farmworkers in Michigan. Only 16 other operations requested PPE from the state during this time.

Farms that have requested PPE from the state have had an average of nine farmworkers per dairy farm, according to the self-reported request forms, which Investigate Midwest received through its records requests.

Conversely, the handful of poultry farms that have requested PPE have an average of 60 farmworkers per operation.

In Colorado, 40 dairy farms have requested PPE from the state agency between the beginning of 2023 and September 2024, according to documents and interviews with the agency.

Most requests came over the summer when Colorado started seeing repeated outbreaks of bird flu at dairy operations. As of early December, the state has had 64 confirmed cases in dairy herds.

The average number of dairy farmworkers operating on Colorado dairy farms that have requested PPE was roughly 40 people per farm.

“Some farms also reported that they had already purchased PPE and therefore didn’t need to make a request,” David Ellenberger, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, CDPHE, wrote in an email to Investigate Midwest.

“Additionally, CDPHE has sent bulk orders of PPE to an agricultural workers outreach group, who has relationships with individual workers, and was able to further distribute PPE on an individual level,” Ellenberger added.

Earlier this year, Texas was the first state in the country to have a confirmed case of bird flu in dairy cattle and, soon after, became the second site of mammal-to-human transmission of the virus in the country.

Since then, Texas has had nearly 30 cases of bird flu in cattle.

The state’s department of health has eight regional offices and it instructs farmers to contact their local office to request PPE.

“Each region fills them as they come in,” Texas spokesperson Douglas Loveday told Investigate Midwest.

In California, which now leads the country in the number of confirmed dairy cattle cases, the health and agriculture departments do not track or manage the distribution of PPE to farms and affected facilities. This task is left to the state’s 58 local health agencies.

In an email, a California Department of Public Health spokesperson said the state supported a one-time distribution of PPE to dairy farms earlier this year. When local requests can’t be fulfilled, the state agency fulfills the request.

As of early December, the agency has fulfilled or is currently fulfilling 43 PPE requests from dairy farms, six from poultry farms and 11 from farmworker organizations.

A similar system is used in Iowa and Idaho, which have also had numerous cases of bird flu in dairy cattle.

Ken Gordon, Ohio Department of Health spokesperson, told Investigate Midwest that when bird flu was detected in northwest Ohio earlier this year, the state made PPE available as the USDA investigated the outbreak. The state received two requests for PPE from agricultural operations during that time.

Now that the farm is no longer being investigated, the state is no longer offering PPE to farmworkers upon request.

“The state-level Ohio Department of Health made PPE available, via the survey, to farms and agricultural businesses on a temporary basis as the situation was new and evolving,” Gordon said.

Other states have received few requests or do not track disbursements:

- As of early December, only one Oklahoma farm had requested PPE from the state’s health department to manage bird flu. The state agency used to have a formal request process for PPE, but it has since closed. “The purpose of this program was to support farms as part of the immediate response until these farms were able to ascertain PPE on their own,” an Oklahoma State Department of Health spokesperson wrote in an email to Investigate Midwest.

- Idaho Department of Public Health spokesperson AJ McWhorter said the agency worked with the industry group Idaho Dairymen’s Association and local public health districts to identify dairy worker needs for equipment and filled a one-time request for PPE for dairy workers in June.

- An Iowa health department spokesperson told Investigate Midwest they direct people to local agencies or to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- In Wyoming, a state with one confirmed affected dairy herd, the health department said it did not track PPE requests or make a request form available to producers. Wyoming Department of Health spokesperson Kim Deti said the state’s poultry and dairy industries are small and PPE requests have been taken on a case-by-case basis.

North Carolina has one confirmed case of dairy cattle infected with bird flu. The state has also seen numerous cases of infected poultry, which is a major industry in the state.

One farm and four farmworkers requested PPE from the state during the ongoing outbreak. The majority of the state’s requests for PPE have come from farmworker organizations and advocacy groups.

The Association of Mexicans in North Carolina requested 2,000 face shields for dairy workers, stating that the association will make PPE available through health fairs aimed at farmworkers and contractors and their families held across the state.

In New Mexico, a state with nine confirmed outbreaks in dairy cattle, only two farms have requested PPE, according to state health department spokesperson David Morgan.

Some major agricultural states are preparing for outbreaks, even if a confirmed case hasn’t been reported.

In Wisconsin, a major dairy-producing state, the state health agency has received 11 requests for PPE from the beginning of 2023 to September of this year. The state has yet to have a confirmed case of bird flu in dairy cattle or humans.

Only one Wisconsin dairy farm and one egg production company have requested protective equipment for employees.

Most of the state’s requests have come from cheese or dairy product manufacturers in the state, as well as veterinary offices.

In addition to workers on farms with dairy cattle, employees who work in dairy processing plants are at risk of exposure to the virus. The CDC states that employees on dairy and poultry farms, dairy processing plants and poultry slaughter plants, should receive PPE to prevent the spread. The virus is destroyed when raw milk is pasteurized at a processing plant.

A spokesperson for Dairy Farmers of America, the country’s largest milk co-op and owner of nearly 50 dairy processing plants nationwide, told Investigate Midwest that the company has a safety protocol to provide PPE for workers at their plants.

DFA was not listed as a PPE recipient in the state of Wisconsin, where the company has three plants.

“PPE is (and was) standard protocol at our plants, prior to the bird flu, as many of our employees work around cleaning chemicals, “ a DFA spokesperson told Investigate Midwest in an email. “To date, we’ve had no requests for extra PPE.”

Wisconsin Department of Health Services spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt, said the agency has worked alongside the state’s agriculture department to provide updates about bird flu to producers, including information on how producers and industry groups can receive PPE.

“We know from our experience across public health that getting resources to agencies, organizations, and individuals who are most trusted by specific populations is the best way to share important information,” she said.

“Producers should continue to enhance their biosecurity efforts and monitor and control disease in their herds and flocks,” she said in an email to Investigate Midwest.

Minnesota’s Department of Public Health has fulfilled more than 200 requests for PPE since May despite the state having far fewer confirmed outbreaks in dairy cattle compared to its peers.

As of December, Minnesota has had 9 outbreaks in dairy cattle herds.

The majority of the state’s requests came from dairy producers, with 138 farms requesting. Twenty poultry farms requested PPE and nearly a dozen processing facilities, either dairy or poultry, requested equipment.

This story was originally published on Investigate Midwest. This article originally appeared in Sentient at https://sentientmedia.org/ppe-dairy-farm-workers-bird-flu/.

Investigate Midwest is an independent, nonprofit newsroom. Our mission is to serve the public interest by exposing dangerous and costly practices of influential agricultural corporations and institutions through in-depth and data-driven investigative journalism. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org